Summary of Episode

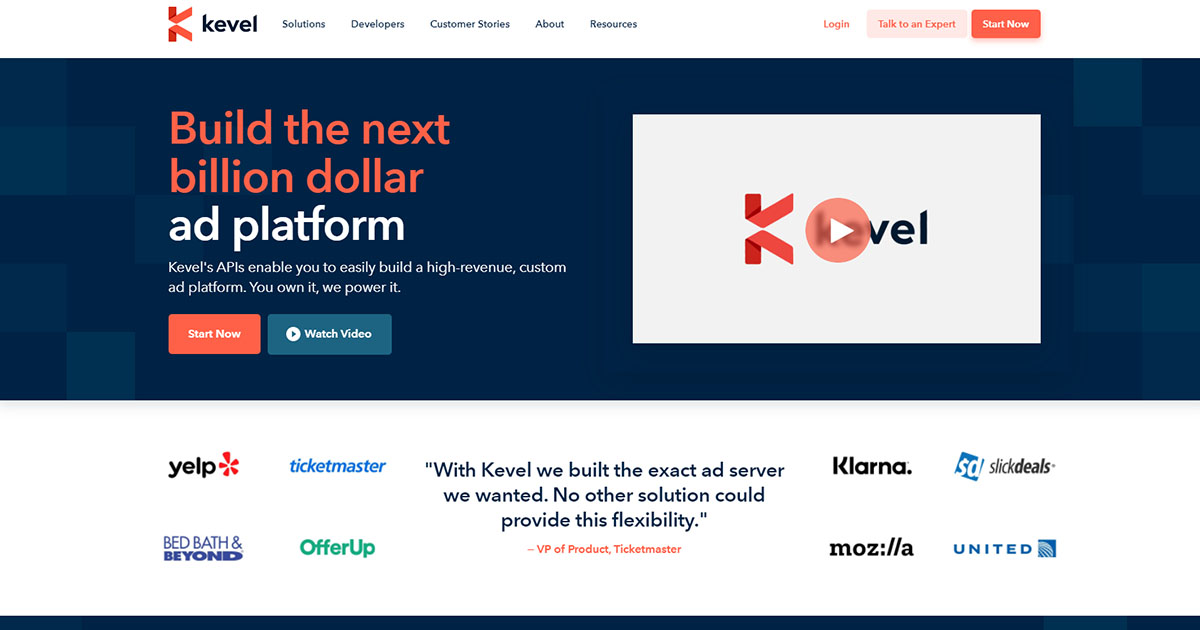

#20: James Avery joins Annaka and Ethan to share his story founding Kevel, a company offering APIs that allow businesses to build their own high-revenue, custom ad platform. James walks us through Kevel’s growth, and we take a look at when it’s best to quit, the benefits of journaling, and how to thrive in a market with big, established competitors.

About the Guest:

James Avery is the founder and CEO of Kevel, which helps users launch their own custom ad platforms. After working as a consultant, James saw an opportunity to build a platform that helps businesses take control over their advertisements. Although it began as a side project, Kevel now works with brands such as Klarna, Ticketmaster, and Yelp.

Podcast Episode Notes

From consulting to building a software focused on advertising [1:02]

Creating the systems needed to allow a company to thrive and prosper in the digital age [3:15]

The mindset required to construct a sustainable, growing company [6:40]

James’s story securing Kevel’s first big client [9:42]

Kevel’s decision to transition to remote teams [14:31]

Building a positive work environment and cultivating company culture while remote [20:44]

Kevel’s approach to advertising — keep it reasonable, seamless, and useful [25:28]

The shifts in the advertisement industry and the importance of targeting [27:53]

Jame’s advice for business owners that want to understand advertisement prices and determine their CAC (customer acquisition cost) [34:37]

“Every rejection felt personal.” Raising $2 million by learning how to hear “no,” reflect, and move along [36:30]

How to know when to endure or when to change? If you can be the best, keep going. If you can’t be the best, pivot [38:55]

Journaling as a way to keep sane and organize thoughts [41:54]

Advising startups and finding advisers who are relevant to your business’s timeline [45:50]

Product-market fit and scaling are two of the main challenges startups continue to face [48:40]

Startups can be lonely for a solo founder. Form a group of peers and create a support network to help you get through the rough phases [50:08]

Full Interview Transcript

Annaka: Hey everyone, and welcome to Startup Savants. I'm Annaka.

Ethan: And I'm Ethan.

Annaka: If you're a returning listener, welcome back. And if you're new, this podcast is about the stories behind startups, the founders who run them, and the problems they're solving. Today, our guest is James Avery of Kevel. We talk about how to foster an epic company culture and hybrid team, the new landscape of web-based advertising, and the art of journaling.

Ethan: Right, and that journaling topic was on point. James gives massive insight on how his journaling and self reflection have made a big difference in his quest to be a great leader. It was really a great conversation and I don’t want to hold you back anymore, so let’s get to it.

Annaka:

Hey James, welcome to the show.

James Avery: Thanks for having me.

Annaka: We're excited to talk to you. I feel like I say that every week, but I'm always excited to talk to people.

Ethan: She is. I can confirm.

Annaka: Confirmed. All right, James, could you start off and just tell us a bit about the history behind Kevel, its mission and how you got started?

James Avery: Yeah. Absolutely. So, yeah, I was a software engineer, as you said, and was kind of doing consulting, working with kind of large boring enterprise companies and was kind of looking for something else. Like as a consultant, you're kind of selling time for money and it gets a little exhausting after a while. You don't get to build something that you really own and iterate on and think about it all the time.

And I also was kind of a content creator. So, I had a podcast and I had a blog and kind of fell into running this small vertical ad network. So, the idea of it was myself and a number of other bloggers kind of banded together to sell advertising to people in our industry. So, we were in the kind of microsoft.net developer space. And so, I was kind of running this small ad network just like on the side. You'd call it like an indie hacker or something like that these days. You had my day job and was kind of moonlighting running this small ad network. And that's kind of how I ended up learning about advertising in general, selling ads, things like that.

And then what I decided to do was really, and well, at the same time I was building the software. So, I wrote all the software to run this ad network. And over time, I realized that the software was a much more compelling business than the ad network. And I thought I could actually take that software and turn it into a full-time job. And that's kind of the origins of Kevel was taking that software. I basically sold the ad network for not a lot of money, but enough to kind of get started. Some people call it like friends and family rounds, but my friends and family didn't have any money at the time. So, this was my approach. And that kind of let me go full time on Kevel early on. This is back in 2010, 2011 and started it back then really with a focus on almost more kind of banner ads and traditional advertising.

But over time really morphed into what we are today, which is an API platform that enables companies to build their own ad platforms. And the reason I'm passionate about it, seems like a weird thing to be passionate about, but I kind of for better or worse grew up on the internet. And I have a passion for what the internet is and that it's free to use and no matter where you are in the world or your economic background, you can find amazing diverse sets of information and ideas on the internet. And that's really made possible through advertising, whether we like it or not.

I'm really passionate about building the systems that enable companies to be prosperous internet businesses and that kind of without someone like us, it makes it a lot harder and you might end up just making all your money from Google or Facebook. And then, you're kind of at the whims of these platforms and Google traditionally takes a large chunk of the revenue, makes it hard to be a traditional publisher. What we kind of espouse is that take it into your hands and go build your own ad platform. But then our APIs kind of help you do that faster for you.

Annaka: Yeah. Those of us that grew up with the internet, we remember what it was like the good old days when even pre-YouTube when literally no one ran it. It was amazing.

James Avery: Yeah. I mean nowadays, I just think about it all the time as a teenager, you could just go read great content. And how often now does somebody send you an article and it's behind a paywall. And to me, that's just a failure of the advertising model because that information should be free and free for anybody to view it. And that's what advertising can make possible.

Ethan: So, you've been at this for a long time. I mean, more than 12 years just on the entrepreneurial side, not to mention this isn't the first company you founded. You've had a successful exit of a previous company, Tekpub. What was it like starting from the beginning and building Kevel from the ground up? Do you have any big lessons for listeners?

James Avery: Yeah. I mean, I think that ... So, I started a number of companies, like you said, and a lot of them were kind of smaller side project turned companies. So, like you mentioned Tekpub, which was a site to kind of have videos for developers kind of like a Pluralsight, who actually ended up acquiring Tekpub. But that basically that started in a bar after an event where me and another guy figured out we were both kind of working on the same thing and decided to work on it together, and did that on the side of also doing consulting and running an ad network. And so, it was always kind of a side project that had some legit success. And then we ended up selling it to Pluralsight.

Starting Kevel, the vision was always a lot bigger. It was always about, how can I build a long-lasting successful company? And that's always been the goal, not kind of like, how do I get to a quick exit or how do we accomplish a small objective. But it was, how do we build a longstanding successful company? And so, starting it out though it was just me starting it and figuring out how to do that.

Ethan: What's the difference in mindset from running those kind of like side hustles as you called them, to saying, "Okay, I'm going to this next business that I do. It isn't going to be the same as these two or three other smaller ventures that I've done. I'm going to make it something much larger." What switches need to flip in your head to go from that smaller scale to something that is more, I guess, large scale?

James Avery: Yeah, yeah. I mean, I think a big thing is just how you go about starting it and capitalizing it and what your goals are. So, with a lot of the smaller projects, it was how quickly can I replace my salary? How quickly can I say, "Okay, what do I need to live?" Well, I don't need my whole salary. I probably need some percentage of it to get by. What do I do? What are the steps I take to get to that as quickly as possible so I can focus on it?

And then you really start to focus on, okay, how do I get back to maybe what my salary was or how do you kind of take these small incremental steps? With Kevel, we really set out to raise money from the beginning and say it's not going to be enough to, my goal is not to replace my salary. My goal is to build a large company and I'm not going to be able to do that just incrementally. In some businesses, you definitely can. But in what we were doing, which was kind of building very complex software, I knew that I was going to have to go higher. And so, from the beginning, it was about raising money, figuring out if we raise money, how do we accelerate growth so we can raise more money and then continue on, on that path. And never really a focus on what are the short-term wins, but what are the choices we make now to set us up for long-term wins. And so, I think it's just a change in your success horizon makes you make a lot of different choices in what you're trying to do.

Annaka: Yeah. And as far as our research led me to believe, at least, I mean, your goals currently are huge. The names that you're looking at, it's like a little David and Goliath here. But Google, Facebook, and Amazon kind of being the, I'm blanking on the word that I want to use and not make it like super, super negative, but they are kind of running the internet right now and their little hands and everything. What gave you the confidence to take them on?

James Avery: Yeah. It's a good question. I think a lot of it came down to at first I started trying to sell it while still running the ad network. And then essentially, I was talking to kind of friends of mine who worked in publishing different industries and kind of getting some interest, but no sales. Until one day, I reached out to a guy I'd kind of gotten to know as part of the ad network, a guy named Jeff Atwood, who goes by like coding horror online. But he is a very popular blogger kind of in the developer space. And he had just kind of recently cofounded Stack Overflow. And he put something on Twitter about looking for an ad server. And I was like, well, this is interesting. So, I reached out to him, had a conversation with him about kind of what I built and that maybe it could help solve their problem.

And he was like, "Yeah, that sounds really interesting. I like you. Okay, but now you have to go sell Joel Spolsky," my co-founder. And so, then I went up to New York, met with Joel, kind of gave him the same pitch. And he was like, "Okay, well, this is the person running it, you got to convince him. And so, then talk to him, give him a demo, give him a test account of this little fledgling ad server I built." And then he kind of comes back a couple weeks later and says, "Well you're missing these 20 things that we would need for us to use you."

Annaka: Wow.

James Avery: "So, I think we're going to have to go with somebody else." And I said, "Well, hold on. What if I can get these 10, the ones you've listed the most important done in the next 30 days, and then the other 10 done by the end of the year." And he was like, "Yeah, I'll give you a shot." And then, I went and basically told my wife like, "I'm not going to see you for 30 days, I'm going to put headphones on and just write code." And I kind of got those 10 features they needed done. They agreed, they signed the contract, they launched. And I was like, "Okay, I just signed kind of on my own when it was barely a company, one of the hottest, new, exciting developer sites, there's something here."

And so then, I think just from that early kind of outsize success. I mean, it took us years to ever sign another customer their size. And so, it was like almost a bad signal in some ways, but it was definitely a confidence building signal that I could go and close and sign up this kind of very well known, well thought of site with really kind of prominent people like Jeff and Joel behind them.

Annaka: Yeah. And why is it important to you to kind of "take back the internet?"

James Avery: Yeah, I mean, I think I kind of mentioned a little bit earlier, but I grew up on the internet. I paid for my own phone line, so I could dial in and not block the phone line for the house. But I definitely didn't have a credit card and I definitely didn't have money to pay for services. And that's really where a lot of my success comes from is being able to play around on the internet and get access to stuff and learn through all these free resources.

So, to me, the real risk to the internet is that we end up back where it's like AOL, but instead AOL is Facebook or Google. And suddenly everything you have to pay for, or it has to run through Google or Facebook. And so, you lose all these great things that could be happening. And people kind of bringing themselves out of not great financial situations through the power of the internet. You can't do that if it's all gate kept by a handful of companies. So, that's why we use "take back the internet" as part of our kind of motto just because we want to make it free and open or keep it free and open in a lot of cases.

Annaka: Yeah. And if anyone is under the age of what, 27, doesn't remember getting the CDs of AOL in the mail, so you could get on the internet, they're like, here's $5 worth of internet time. I don't know. Kids these days have no...

Ethan: Yeah, I know. You walk into your local JCPenny, and your mom is looking to get your school photos taken and you pick up a CD out of a cardboard case that contains the entire internet on it. And now, it's just not quite like that.

All right. I want to talk a little bit about your team. You've got, give or take an 85-person team that's distributed through at least a few countries. Excuse me, I believe primarily in California, North Carolina and the UK. And those are the folks that are helping you take on these giants in the industry. Is your team completely remote or do you have in-person offices and what goes into making a decision like that?

James Avery: Yeah. So, originally, we were all in the same place, which is Durham, North Carolina, kind of part of the research triangle Raleigh Durham area. So, we were all in the same place in the same office. And then kind of after a couple years, we had the opportunity to hire somebody who had worked at one of our customers and he was based out in San Francisco. And from a sales perspective, that was a great rationale. We're going to hire a salesperson out in San Francisco where we have a number of customers, have somebody kind of on the ground, but he was the only remote person for a while.

And then what happened was we had one of our engineers decided that, for family reasons, they had to move. And we were like, "Wow, we're really going to let this great engineer leave just because he can't live within 30 miles of our office." And so, "Okay, we'll try it." And so, we kept him on remote as he moved, he moved out to California. And then we just, that was kind of the way it snuck in the door. And we started just hiring kind of more and more remote, but also continued to hire a lot of people in Durham.

And so, kind of pre-COVID, we had probably about 15, 20 people in Durham in an office. Most people came in, I'd say three to four times a week. And then we had about 10 or a dozen people kind of spread across the US. And we had just made our first couple hires in the UK. And then when COVID happened, obviously everybody went on full remote, learned to live on Zoom. And then we just really embraced it and said we were going to double the size of the company or really triple the size of the company. Do we really want to limit ourselves to hiring people within 30 miles of an office?

And so, we just really opened it up and said, "We'll hire people anywhere." And so, we started hiring. We have people in, I don't know, over a dozen US states. We've got 20 plus people, I think now in the UK. And I think it's been great. I think I do miss the office. Every once in a while now, some people will go back into the Durham office, but because the teams are so distributed, you can go to the office and nobody you work with will actually be there, it'll be people from other teams.

Ethan: Right.

James Avery: And so, yeah, I think we've really gotten used to living on Zoom and Slack. And then also making time to get together. One of the things we did this year was to create a budget for team off sites. So, every given team can choose to just go anywhere in the world to meet up together, as long as it's within the budget, which means it's not you're not choosing Fiji because it's not going to fit your budget. So, a lot of times, it ends up being somewhere that like people don't live, but is interesting.

Ethan: Cool. I've heard a few of these companies that kind of have hybrid office setups, is that how you would describe your company as hybrid at all?

James Avery: I mean, I think today it's still almost full remote. I mean, we have an office in London, but there's really only a couple people that tend to go in. We have one in San Francisco that I don't know that anybody's going into right now, but we still have a lease. And then Durham, I think it's pretty sporadic. So, I would say we're mostly full remote at this point. I think the hybrid model, that's what we used to do. Pre COVID we were hybrid, which was definitely more difficult. We had a member of the leadership team who was remote and everybody else was in Durham.

And so, they were always the talking head on the wall meeting. Or would miss out on that we end the meeting and then you have 10 more minutes of conversation in the conference room. And so, I think it's like hybrid can be really hard to do, especially if one or two members of a team are the only people remote, that's really tough.

Annaka: Yeah. It's a struggle to kind of the team is together and working together when everyone's remote, the team is together and working together when everyone's in the office, but you have half and half it's like, wait, how do we work together now? This is weird.

Ethan: Yeah. You can kind of create kind of a two class system in some companies if you do have that kind of split of folks in the office, distributed people. So, it's good that you're kind of skipping that headache.

Annaka: Yeah.

James Avery: Yeah. Even though I think, I see a lot of value in working together in person. And so, I do think if you, when you go remote, it is so valuable to get together. Just like this week, I was in New York for a conference and one of our PMs is there. And we just grabbed a room at like a WeWork for three hours to just whiteboard stuff and talk through things. And it's so refreshing to do that in person. So, it's like invigorating, whereas sometimes sitting on Zoom can be draining.

Ethan: Oh, yeah.

Annaka: Yeah. Just seeing people in yeah, in person again, it's like, "Oh my god, you have facial expressions and body language. And I'm not seeing you with your camera off, your avatar or whatever." So, I fully understand that. And you mentioned a little bit about culture having a budget for offsites and y’all were named on Inc.com's list of best workplaces. Can you tell us more about how you managed to create such a positive work environment, especially when you're fully remote?

James Avery: Yeah. Absolutely. I think it all started back when I was starting the company and first started hiring people. I just asked myself like, if I was designing where I'm going to work, because technically I do just work here. We have investors. We have a board. I'm not an owner. How do I want to work and how do I want to be treated? And so, like one of our first or our first values as a company is that we're all adults. And so, it's just this approach of it doesn't make any sense if you need to run to the post office that you should have to tell somebody. Or that if you are going to take the afternoon off, you shouldn't need approval to do that. Or that we kind of trust our employees to make good decisions versus trying to legislate them and give them every little rule here and there.

Really try to build on autonomy and give people the opportunity to decide how they want to work or when they want to work. And it's less about being in a seat. As a consultant, it was so frustrating where it'd be like, you need to be in at 8:30 and then make sure you don't leave before 5:00 because the guy who pays the bills sits by the door. And I'm like, "Shouldn't we be judged on if we're successful or not?" And so, that's what I'm trying to bring into the company is just that we know the job we need to get done or do, and it shouldn't matter when we work to get that done. And we should trust ourselves and trust each other that everybody is working hard because we're all motivated to do a good job and not be, "Oh, so and so took vacation again," or, "That's weird, they didn't get on Slack until 10:00 AM." I have no clue when people get on Slack. It's a matter of, we set some goals, are we hitting these goals?

And then I think the other part was looking at things like benefits we pay 100% of healthcare for our employees and their families. And one of the goals there was just like, I don't want to worry about it. I don't want our employees to worry about it. If they're going to worry, like let's worry about company stuff. Not like can you pay a doctor's bill? Or if you're sick, can you afford to go to a specialist? We try to cover and make it so that you don't have to worry about that stuff. And so, I think kind of between the cultural, we're all adults, and then also being very trying to enable people to focus on either their family or their job or their hobbies, but not these other things, like how am I going to pay for this insurance and stuff like that.

Annaka: And did you go into starting with these kind of culture frameworks in mind or was there any kind of feedback loop you were working with, hearing from your own employees, like, "Hey it'd be really nice to get together." Or was this just stuff that you picked up along the way to kind of create this culture?

James Avery: Yeah. I think when I was starting it, I had some kind of key things in mind, especially around autonomy and being adults. And some of that I pull from if you've read the Netflix, their culture code presentation. I remember reading that and being like, "Oh, this is a company I want to work at." And then instead of going to get a job at Netflix, I say, "Wow, start a company and try to follow some of these same guidelines and approaches to things." But then a lot of the rest has been learning over time. And I think the meeting in person in a large part was, oh, I really miss meeting people in person. How do we facilitate this? How do we get this done?

Annaka: Yeah.

Ethan: It's amazing how these ... I've also heard of that Netflix culture deck. I think it's kind of made its way around the internet. I haven't heard about it in the past couple years, but it's really amazing that these private company documents will go out there and create such a change for so many different companies in the world. Maybe someday we'll create something that accidentally gets leaked and we'll change the world.

Annaka: Yeah.

James Avery: I think it was intentionally leaked, but they made it look. I don't really believe it was fully accidentally leaked. I think that might have been intentional.

Annaka: Yeah.

Ethan: All right. Let's dive into the foundation of your company, which is ads. What are some of your secrets to building and launching a successful ad campaign, of course, besides using Kevel?

James Avery: So, yeah. I mean, the way we think about ads is really, I think kind of simple, which is, is it reasonable and is it not ridiculous? Does it feel like a normal part of the experience? I think when you look at the best performing ad platforms, they've managed to bring ads into our lives in ways that aren't super intrusive that sometimes are even useful or helpful and that feel relevant, but then also aren't slowing down the site or invading your privacy.

And so, the way we kind of think about it as the creepiness factor. If you go search on Google for something and then you see an ad for it, that seems very reasonable. Or if you go to Ticketmaster, which is one of our customers and you see an ad for a show from a band that you've seen before, very reasonable to you. You're like, oh, I'm logged into Ticketmaster. They know who I am. They know I saw this band before and they're showing me a promotion for the band because they're coming back to town. That's a very useful ad even if maybe the band or someone else's paying for it. And so, when we work with our customers to kind of build ad platforms and when they're building ad platforms with us, the question is always like, how do you build that perfect ad where it is seamless and non-intrusive and almost useful to a customer?

So, promoted listings are another one. If you go to Amazon, you search for products, they'll be promoted listings in the search results. They're targeted. They're what you're looking for. Maybe not the specific thing. You might be looking for a different brand, but it doesn't feel out of place. And you've told them what you're looking for. For us, a lot of it too is like, where do you stay away from? Which is where you look at a pair of shoes and then it's tracking you across the internet and showing you those shoes everywhere. Even if you already bought them or if you were just making fun of them. Then they still think you wanted them.

Annaka: I think you're good. I think we all know about that when it's like, man, that really ugly shirt from three weeks ago will not stop following me around Facebook. Fine. I just want to highlight the differences between web advertising where we want it to be like kind of unobtrusive. We're just mentioning this as you're consuming here on the internet versus print where it's like, if it's bright orange and 40 feet tall, that's how we get your attention in a physical advertising space. So, just as a nerd, wanted to point that out as being like, wow, things have changed in advertising.

James Avery: Yeah. But even it's one of my favorite examples is Vogue magazine, where a big part of Vogue magazine is actually the ads. A lot of times people who buy the magazine, they read the articles. But a lot of times, they're just looking through to see like, what new products are in here? Who's modeling for who? It's like the ads are actually this very integrated part of the experience of Vogue magazine. Or, people who like cataloged like a great thing. You want to go flip through. They're just ads that got sent in your mail. If they're on target, you're excited to get that catalog and say, "Oh, I'm going to look through this catalog of Jeep parts or whatever it is."

But then, if it's like if it's not targeted, you're like, "Why did they send me this catalog for like baby clothes? My kids are like 10, what is going on?" So, I think the internet's a lot of the same thing, like with Facebook and especially with Instagram, they did a good job with a lot of the advertising where if you're flipping through or TikTok, you're flipping through, a lot of it feels very targeted and part of the experience. Whereas I feel like whenever it's very jarring, it's just a bad experience for everybody. If you're playing a game on your phone and then they're like, you have to watch a 30-second video ad, you just want to, you just close the app. You're like, I can't live my life like this.

Annaka: You don't want to watch an ad about another game, I'm playing a game.

James Avery: Yeah, exactly. And I think, over time, you see that the best apps like YouTube, before you could skip ads, were miserable. The same with TikTok, you imagine if you're watching, you had to watch the whole ad. You can just flip by it if you're not interested. Those kinds of experiences still really work for brands because if you are interested or if they've built a really good ad, then you will watch it, because if it's interesting to you. So, when we talk to customers and we say, "Go build this ad platform," or they want to build an ad platform, we're not telling them to. We kind of look at like, well, how do people use your software?

If they're using it to research cars, well, how do you let used car dealers promote cars that match what they're researching? Or how do you let Nissan target people looking at Hondas to kind of pitch like, "Hey, maybe you should look at a Nissan." These sort of things that feel relevant and you might say, "Oh, you know what, actually, I didn't know that Nissan looked that cool. I always thought they looked like this." And so, I think that's the real lesson is to find ways to bring advertising and make it useful, not intrusive and not a terrible experience.

Annaka: Yeah. I mean, now that I think about it, I spend a lot of time on cooking websites and things like that. And then, yeah, just miraculously, there will be a list of 150 kitchen products that I might need. And I'm like, of course I need that. Of course, I need a dinosaur ladle whose name is Nessie. Yeah, I do need that, so touché.

James Avery: Yeah. I mean, there was a recipe website we used to work with where they would let people promote the ingredients, which was just like a simple way of doing things, which was just you're looking at a recipe already and it says you need mayonnaise and they'd let put the Hellmann's logo next to it. That's not annoying you. Actually, visually, it's kind of nice because you see the Hellmann's logo and you think, "Oh, it's mayonnaise."

But it's also kind of brand reinforcement and thinking, oh, when that Hellmann's you equate to mayonnaise or Heinz with ketchup. Those sort of things can be effective for brands, but aren't annoying. They aren't an ad blocking it. So, if we try to print the recipe out and all that prints is like an ad, all this sort of stuff. There's ways to do it in very integrated ways that are good for the experience.

Annaka: Man. Now, I'm going to keep an eye on it. It's like when I first heard about product placement in movies and I'm like, "Look at that slow zoom out on the BMW logo. Gotcha." All right. So, we're going to pivot a little bit for our listeners. We're recording this in May of 2022. And James, we'd like your thoughts on this because we may be looking at kind of a financial slowdown or correction in the market. What do you think that the impact or if there would be an impact on ad spend in the next coming months and/or years?

James Avery: Yeah, I think ad spend stays pretty consistent as a percentage of GDP. And so, if we do go into a recession, you could foresee see ad spend decreasing along with GDP. But usually it's not something that tanks way ahead or anything like that. And it's not something that is really super tied to the financial markets or growth. Every company is going to be looking for ways to continue to grow and grow faster and they're going to spend money in advertising to do that. So, I think that you'll also see, I think even more companies embracing advertising because there's a lot of businesses that were built kind of in the very good times of the last five or six years and have unprofitable business models and are now saying, "Oh, actually advertising is how we help to build a more profitable business."

So, you see lots of food delivery companies launching ad platforms because it's hard to make money bringing new McDonald's. But if you can build an ad platform because so many people come to your app when they're looking for restaurants, then that becomes a very profitable area.

Ethan: Do you have any recommendations to new founders out there who are kind of looking to understand the market that they're about to get into? Do you have any ideas on how they based on their product and their industry, how they can kind of guesstimate what their CAC might be, the Customer Acquisition Cost? Do you have any tips for that?

James Avery: I mean, I think that before I would start anything, I would go and buy ads against it on different platforms to see if you're going to enter into a business where there really is a strong advertising component, then I think you can go and target those keywords on Google and target your demographics on Facebook or Instagram, set up a simple landing page, pay for people to get there and see how much it costs you to get somebody to put their email in. And so, that's a one way to kind of just look at what is it going to cost me to pay for users. And I think one of the things too there is to really explore different platforms because over time, like Google and Facebook, it's like its own economy where it gets to the fair value of what that user costs.

And so, for certain things, if you're going to go launch new help desk software, you're going to pay what it's worth to Zendesk and Intercom and all the other people in that market. But sometimes, if you go find a new platform, if you go to Reddit or you go to one of these newer platforms, you might be able to find kind of an inefficiency and acquire and run advertising for a lot cheaper than you would for the same users at Google or something like that.

Ethan: Awesome. Appreciate that tip. All right. Let's go back to the beginnings, the beginnings of the company. In the profile that people can go check out on startupsavant.com, you mentioned that when raising money, every rejection felt personal. But clearly at 22.2 million in funding, that really hasn't hindered your success in fundraising. How did you overcome taking that rejection personally?

James Avery: Yeah. So, I think coming from an engineering background, you're much more used to kind of controlling your success. And a lot of times it's like, I just need to put more work in or I need to learn more and I'll figure this out. I'll fix this bug or I'll ship this feature. When you get into fundraising, it's really sales. And so, people who have a sales background usually are pretty natural at fundraising. Partially because yes, you're in the room, you're trying to sell investors on investing in your company. But also, because sales is predominantly rejection. A lot of people forget that with sales, where it's just the people who close 10 deals this week, they probably heard no 90 times or more.

And I think that's the part that if you're not in sales, every time you're out fundraising, you just keep hearing no. You're just like, "Oh, what did I do wrong? I did something wrong. My company sucks. What are all the things that could be wrong?" Whereas an experienced salesperson thinks of it as like, "All right, what did I do wrong? Okay. I don't think I did anything wrong. Okay. On to the next one." Some self-reflection, is there anything to learn? If not, on to the next one. And they know it's kind of more of a numbers game.

Ethan: Right. Yeah.

James Avery: I think that's something fundraising where you just got to get used to like that, yeah. It's a numbers game too.

Ethan: Right. How many nos does it take to get to a yes, that type of thing.

James Avery: Yeah. And even when you look back at stories from, was it like the Airbnb, Brian Chesky, was talked to a hundred people before somebody invested in Airbnb. Everybody has these numbers of talking to 50 or 80 or 100 investors. And I talked to too many founders who have six meetings, everybody says no. And they're like, "Well, I guess it's not a great idea." Or you just six out of a hundred. So, your odds of hitting that person in those six was 6%.

Annaka: And there was something that you'd mentioned in your company profile about the need to endure through setbacks. So, you're kind of leading that direction. How do you tell the difference between needing to endure through a setback and needing to change your approach?

James Avery: Yeah. That's a great question. So, there's this book by Seth Godin called The Dip, and it's one of my favorite books. And I usually read it every year because it's also only like 30 pages. So, nobody has an excuse to not read this book. And one of the things, it's like in The Dip is kind of talking about when things are hard, when things got hard, how do you decide if you should quit or you should keep going? And that's not just about the whole company. It can be about any given thing. It can be like about a strategy that you're trying or a market you're going after. How do you know when to quit? And my favorite quote from there is basically, I’m going to paraphrase it now, but it's like quit or be exceptional. Average is for losers.

And so, basically I think the way you can look at it is and sometimes something could be slightly working or kind of working. And I think the best way to think about it is like, can I be the best in the world at this? And if I believe that I can and that we see a path to that, then that's really worth striving for. If we're working really hard and striving really hard and we're best case scenario, we're number five, this isn't worth that. And it's going to be really hard to get to number five in this competitive market.

And so, for us early on, we were really in display advertising competing almost essentially directly with Google. And it was just really, really hard and just the slog. And after a while you're like, can we really be the best in the world in this versus Google who has all these kind of unfair advantages that they've bundled in demand. They're world search leaders. Or do we need to find what we can be best in the world at? And that's really where we looked at our customers and said, "Oh, most of our customers are using our API." Google's not focused on helping people build ad platforms because they want people to use their ad platform.

So, it kind of helped out guide us to like, well, we can be the best in the world at helping people build ad platforms. Whereas we were never going to be best in the world at display, just because Google is going to be that. We're not going to go build a better search engine than Google either. So, yeah, that's kind of how I look at it. It's like, can we be the best at this? And that's when it's worth fighting for and going through the struggle.

Ethan: I want to segway into something a little bit personal. You've mentioned that you have a strong journaling process. Can you tell us a little bit more about that and how it's helped to lead to your personal success?

James Avery: Yeah. I don't know if it leads to my personal success. It definitely helps with personal sanity. So, for me, I think a big part of I've always enjoyed writing and I think it really helps you organize your thoughts. It's almost like free therapy if you write something down. And so, what I do is almost every morning, actually, every work morning, actually I don't do it on weekends. It's my break. Every work morning, I sit down in the morning and just write about what I'm thinking about, what I have coming up for the day, what are the big things that keep rolling around in your head? And I think it just helps me organize my thoughts for the day.

And then I'd say the reverse is that I don't always do this, but sometimes if you're trying to go to sleep the best cure if you can't go to sleep is just to write everything down that you're thinking about. Because sometimes it's like that hard problem at work will just keep tumbling around your head and you're trying to sleep. If you go write it down, then usually you can go to sleep.

Ethan: Right. Yeah. I think it was David Allen in Getting Things Done that says, "The brain is not meant to store things, it's meant to come up with new things." So, taking those things that you're trying to store in your brain and putting them on paper somewhere where you're not going to lose them, that's, oh my gosh, it just clears up so much space.

James Avery: The only downside I'll say is that I never go back and reread any of it.

Ethan: Me either.

James Avery: And so, if I go right down a list of here's some things I need to get done, my brain is like, great. We wrote that down. And it's gone and I never do those things. There's some downsides too. Speaking of David Allen, I could probably reread that book and maybe get a little bit better about task management.

Annaka: Yeah. It's like once it's out of your brain, you did not have permission to forget that.

Ethan: Yeah.

James Avery: Which is good. But a dangerous weapon if used incorrectly.

Annaka: Yeah, yeah. It's like, okay, you can forget about how anxious you are about this meeting, but don't forget about the top five things you need to do in the morning. Not good.

Ethan: I just forget about the meeting itself and then I'll show up.

Annaka: That is so true.

James Avery: That works too. Yeah.

Annaka: As far as journaling for people that maybe haven't started, do you have any kind of like go-to questions that you might ask yourself or any kind of routine that you might follow to get journaling started?

James Avery: Yeah. I remember I found a site that had different journaling prompts when I was first starting. And you kind of pick a prompt for the day. But then now I just kind of, it's like, whatever's top of mind. I don't really rely on the prompt. And sometimes the prompts are kind of awkward and you're like, that's not what I'm thinking about at all. A lot of times, it's just that it's what are the five things rolling around in your head that you're thinking about you need to do or the hard problems or the people problems or how you feel about something that's going on? And it's just a great way to get all that out and think through it.

Annaka: Yeah. Now I'm wondering if they still make locking diaries from back in the day so that I can lock it away?

James Avery: Founder Diary, there you go. You could start a little company, like a DTC brand.

Annaka: All right. Let's do it. Let's do it. All right. Back to startup things, you are a startup advisor as well, right?

James Avery: Yes, yup.

Annaka: Okay. So, how did you get into that? And do you recommend that other founders take on a role like that as well?

James Avery: Yeah. So, I got into it because there was an accelerator starting in Durham by a friend of mine, Chris Heivly. It's called Startup Factory. And he invited me to come be an advisor. And I remember I was like maybe two or three years into running Kevel. And I was like, "Well, I don't know. Am I really who you want? You have all these really successful people." And he's like, "No, your advice is way more valuable." He's like, "Because most of the people, if they sold their company or had their success 10 years ago, it's like so much of their experience is not very relevant."

Ethan: Absolutely.

James Avery: And that's where I learned that actually the most valuable you can be as an advisor is if you lived what they're living like a couple years ago. Because it's like relevant, you have enough perspective so that you know how things went. And then I think you can really be a lot more helpful. I also think that a key part of being an advisor is just relating experiences versus telling them what to do. And I think a lot of times, that's a newer kind of convention. A lot of times, if you have somebody who did something 20 years ago, they're going to be like, "Well, I did X, Y, Z. And you should do this." Or, "I've heard this TikTok thing."

Whereas it's so much more useful to just say, "Well, two years ago when I was fundraising, here's what I did. Here's what worked. Here's what didn't work. Here's when I cried myself to sleep. And here's what [inaudible] be," and relate the experiences and kind of what you learned as opposed to just trying to tell what to do.

Annaka: Yeah. It's funny enough, that's how we end up choosing a lot of our founders that we have on the show. It's like they're not done. They're not hugely successful multibillion dollar crazy things that can't relate to people that are just starting out. So, I think it's a really, really valuable relationship.

James Avery: And I think it changes over time too. I've noticed, I'm still an advisor for companies, I'm definitely more useful. I'm less useful now if somebody's like, "I have a new project to start." And I'm like, "Oh, it's been a long time since I did that. I know what I hear and what I read, but I haven't done that in a long time." Whereas if I talk to somebody who is looking to raise an A round, that's all fresh in a similar environment. And I can talk to them about that and share how I did it. So, I think there's definitely like a sliding scale. And then like, I look for advisors and people who are a couple years ahead of me.

Annaka: Yeah. And are there any kind of recurring or common challenges that you see startups facing these days?

James Avery: Yeah. I mean, I think that, I mean, hiring continues to be one of the hardest things, especially as we all move to remote and everybody's competing with everybody for better or worse, hiring might get easier soon if the economy turns down and things like that. But then I think a lot of times the number one challenge is always just product market fit and scaling. The biggest challenge is getting to that point where you're like, I can repeatably sell a customer and then figuring out how to scale repeatably selling a customer. Those seem to be the two big challenges that most people are facing.

Annaka: Yeah. Even in the internet ecosystem, it's still a difficult thing. All right, James. So, what is next for Kevel?

James Avery: Yeah. For us, I mean, right now, we're just thinking about how do we continue to scale and work with larger and larger customers, sign more customers, and keep growing the team. At this point, it feels like it's kind of like the flywheel of where once you get it going, the job is to just keep pushing it faster and faster. So, that's a big goal for us is just keep doing what we're doing and do more of it and continue to invest in the company.

Ethan: What was the thing that most surprised you about entrepreneurship?

James Avery: I guess because maybe because I'd done a couple smaller startups, it definitely wasn't any of the like logistics. I'd gotten used to understanding like I know more about taxes and accounting and insurance and all those things than I ever should. I think probably the biggest thing is that it really can be like a lonely thing, especially if you're a solo founder that you're always, I think that's when I look back, I think I don't know that I would go back if I would have a cofounder or not. But I think if you're founding something on your own, it is very lonely from the sense that you're at the end of the day. It all comes back to you.

And you can make terrible decisions and there's nobody else you can blame it on. It's all your fault. So, I think that probably was a little bit surprising to think that even when you have a company that's 20, 30 people that you can still feel kind of isolated because of your position as a founder.

Ethan: Right.

Annaka: What do you do in those situations when you're feeling like you don't have a cofounder, you can't just go to the cube over and be like, "Hey, will you please listen to me for 20 minutes?" How do you get that out?

James Avery: Yeah. One of the things I did early on, which I highly recommend to everybody, is to form a group of peers that you can trust. And so, there was a handful of companies that were starting in Durham at the same time. And I really got to know three other CEOs. And we would kind of meet for breakfast or we'd meet for drinks, and just complain to each other.

And say the stuff that you don't want to say to your team or kind of have that peer group I think is really, really useful when we were smaller. I think as you get larger, what I found was that really is to as you hire other leaders that you're going to bring on the team to really be able to confide in them and treat them like a peer group, as opposed to thinking that you're the founder and that you have a different status or something like that.

And so, I think early on, it definitely will feel that way. And so, find that peer group. And then I think later on is really to build a leadership team that you can trust and confide in and that you can just go to the cube and be like, "Oh, can I complain to you for 10 minutes?" And it's not like a bad thing. They're used to that or you have that sort of relationship. So, yeah, I think those are the two ways.

Annaka: We do hear that pretty often that leadership can be isolating, so make friends.

James Avery: Yeah, exactly.

Annaka: And what other advice do you have for entrepreneurs that are just starting out?

James Avery: Yeah. I mean, I think the number one thing I always tell people is to read and learn more than be voracious in how you kind of go consume information. But also, be wary about just taking advice from Twitter and short blog posts. There's great books out there that really take the approach of saying, "Here's how great companies are run. Or here's things that you can really learn and dig deep on a topic.” Go read all of those. As opposed to sometimes I feel like there's off the cuff little wisdom people try to get from whatever they read on Twitter or blog posts.

So, for me, I always recommend Good to Great, which is just this amazing book I think about building and running successful companies. And then books like Drive by Dan Pink, which is so good about managing people. And then I think Seven Powers is a great business strategy book where I think a lot of people when they go set out to run a company and if they don't have an MBA or something like that, they don't really think about like, what are the choices? What is my long-term strategic advantage going to come from? And yeah, you can't do all that today, but it's really good to be thinking about those things early on. Because I think it can help you really avoid early mistakes.

Ethan: All right, James, this has been a ton of fun. I think there's been a whole lot of really great knowledge shared in this and we really appreciate it. We have one more question. No, this is a really tough one, so be prepared. How can our listeners support you and Kevel?

James Avery: Yeah, I mean, I think go to our website, kevel.com, look at what we do. If it applies to an industry that you're in, if it seems interesting, reach out. I would say otherwise, just continue to use the internet, which I think is really easy for everybody to do.

Ethan: Awesome. Well, we'll put those links and the show notes to all of the books and everything else that was mentioned today. But that is going to be it for today's episode of the Startups Savant podcast.

Okay listener, let's have a quick chat here by this fireplace. I just want to thank you for always being there for us through thick and thin, bad times and good times. I really truly treasure this friendship that we share. And since we're sharing, we'd like to hear what you think. How are we doing? Do you like the folks bringing on? Do you like the conversations we're having? Do you like us? Send a message to podcasttruic.com and let us know. And if you do really, really like us, check out that rating sections of the Apple Podcast app and drop us a five star rating. That would really make my week.

Annaka: And mine, too.

Ethan: For tools, guides, videos, startup stories, and so much more, head over to truic.com, that's truic.com, T-R-U-I-C dot com. See you.

Annaka: Bye.

Tell Us Your Startup Story

Are you a startup founder and want to share your entrepreneurial journey withh our readers? Click below to contact us today!

More on Kevel

Innovative Tools for Building Custom Ad Platforms

We’re going to discuss how Kevel got started, how they developed their startup, and what they have on the docket going forward into the near future.

Founder of Adtech Startup Kevel Shares Their Top Insights

James Avery, founder of ad tech startup Kevel, shared valuable insights during our interview that will inspire and motivate aspiring entrepreneurs.

Here’s How You Can Support Adtech Startup Kevel

We asked James Avery, founder of Kevel, to share the most impactful ways to support their startup, and this is what they had to say.

Kevel Company Profile

Kevel is an adtech startup that creates custom ad platforms for companies looking to launch impactful ad campaigns.