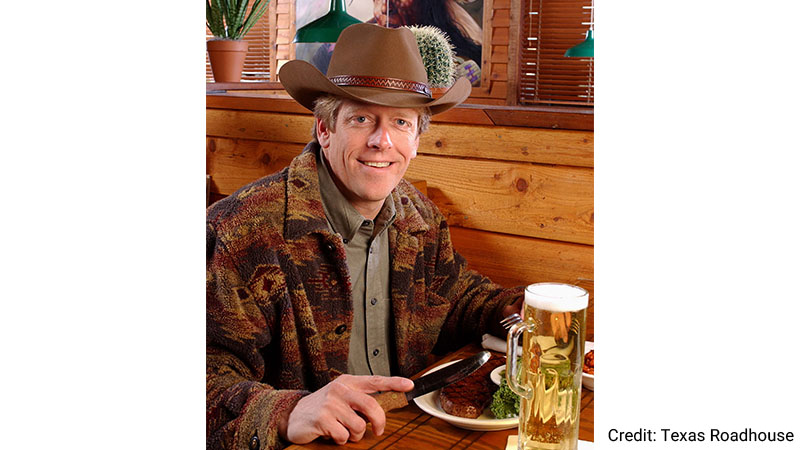

Kent Taylor Cooked Up the Recipe for Success With Texas Roadhouse

Startup Savant normally covers living leaders and authors, but we're making an exception for Kent Taylor, an exceptionally unconventional entrepreneur who completed his memoir shortly before his untimely death in March 2021.

“Made from Scratch: The Legendary Success Story of Texas Roadhouse” is the extraordinary tale of how, at 39, he reached an agreement with three dentists to fund his vision of a "blue collar cowboy steakhouse" chain after 130 unsuccessful pitches. They opened the first in 1993, but within a couple of years, two out of the first five locations had failed.

Today, Texas Roadhouse and its affiliated restaurants, Bubba's 33 and Jaggers, have 620 locations so far in 49 states and 10 countries, with a 99% rate of success. That compares with a pre-pandemic track record, according to Modern Restaurant Management in 2019, of 60% of new restaurants closing within a year and another 20% within five years.

Lessons From Real Life

After the painful experience of the early closures, Taylor decided that maybe he had missed something before he flunked out after his first year trying to get an MBA, so he hit the books. Back in 1990, when he was an area manager for KFC in Charlotte, N.C., he was chastised by a boss for trying to be too innovative. He recommended Taylor start his own restaurant and gifted him with Stephen Covey's “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People” so he could understand what it would take to become an entrepreneur.

Some years earlier, Taylor had been inspired by Norman Vincent Peele's “The Power of Positive Thinking” and now began reading every motivational and business book he could find. In his own volume, he devoted two appendices to lessons from his favorites, and you could best read it starting there for its concentrated wisdom before immersing yourself in what is probably the most entertaining and earthy entrepreneurial account ever written.

"Each year, there are hundreds, if not thousands, of books written on leadership, from heads of companies to business school professors to Navy SEALs to curling coaches," Taylor wrote. "I typically read a dozen or so each year and many have helped me better define my own thinking on what it takes to lead a team effectively … The best business owners and executives I've ever met are voracious readers and students of leadership … If you study any of the most successful entrepreneurs and leaders of the last 100 years, you'll be hard-pressed to say that leaders are born. Most are made. I believe the inner spirit to inspire others lies dormant within all of us."

No doubt, lists of resources for how to be successful include his reference to a 1944 report by the Office of Strategic Services (predecessor to the C.I.A.). It was a war-time guide on how to sabotage the decision-making processes of organizations, and among the tips were to do everything through proper channels, form lots of committees, and refer back to earlier decisions (Taylor updated it with "cc everyone"). At the other end of the idea spectrum, he wrote that “The Book of Joy” by the Dalai Lama and Archbishop Desmond Tutu helped him live a fuller, more empathetic personal and working life.

Some of his favorites about or by entrepreneurs are not surprising for a self-described "crazy" practitioner, such as “Nuts” by Kevin and Jackie Freiberg (about Herb Kelleher, founder of Southwest Airlines, who became a mentor), Nike founder Phil Knight's “Shoe Dog,” “Onward” by Howard Schultz, Sam Walton's “Made in America,” and “Steve Jobs” by Walter Isaacson. But also listed are basketball great Bill Walton's “Back from the Dead,” coach John Wooden's “The Wooden Way,” and Willie Nelson's “It's a Long Story” (the first two spoke at Roadhouse conferences, and Nelson is a not-so-silent partner).

The good ideas from all these sources that can be widely applied to business and life in general fill bookshelves, but these are some of Taylor's core ones (a list of tips at the end of each chapter about the history of Texas Roadhouse elaborates how these and others played out in the real world):

- We all have two ears and one mouth, which is God's way of telling us to listen more than we speak.

- Get rid of negative influences and distractions, minimizing time watching TV and being on social media.

- Be honest and have integrity.

- Be courageous, whether it is speaking out in a meeting or doing what you feel is right, even though everyone else disagrees.

- Make your values clear and be authentic.

- Align your mission statement with your policies and practices.

- Hire for attitude — everything else can be trained.

- Every employee should think like an owner, and everyone should take responsibility for their actions.

- Don't let rules, systems, and procedures turn a lean organization into a bureaucracy.

- Be decisive to get results before it is too late.

- Take a sincere interest in others, including their knowledge.

- Become a lifelong learner.

- Find mentors (Taylor had dozens, both famous and known primarily to business leaders).

- Persist, persist, and persist to overcome adversities.

- Have a clear vision of what your long-term goals are.

All of these things seem obvious, but few are practiced like they should be at most companies, where management is disconnected from their frontline workers (not to mention customers): a 2017 Gallup study found 55% to 80% of people said work is something they endure, rather than enjoy.

"In tough economic times, it is easy for CEOs (pressured by boards and large shareholders) to cut quality or people, and lose their culture in an effort to preserve their precious quarterly bottom line," Taylor wrote. "The long-term damage to their brands for this short-term thinking usually becomes clear a few years later when they are shown the door … I can't help chuckle reading their BS public statements about spending more time with their families or pursuing ‘other opportunities.’"

So did he miss something at business school? From reading and experience, he concluded something that probably wasn't taught in any class. As bestselling authors Adrian Gostick and Chester Elton write in the preface, it was best to "avoid hiring anyone with an MBA or a Ph.D."

The Long and Winding Road to the Roadhouse

Born in Richmond, Virginia, in 1955, Taylor’s family moved to Louisville, Kentucky, where he started as a freshman in high school as a 5'2", 110-proud aspirant to the cross-country running team. By his junior year, he was running six to eight miles a day, "getting out of my comfort zone and pushing through the pain of accelerating up hills," and received a partial athletic scholarship to the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.

But he partied too much and barely earned his business degree, then doing worse in Lexington, Kentucky, where he took summer courses for his MBA. He turned to his one real skill, bartending, and his entrepreneurial Uncle Bill hired him to manage some nightclubs. Taylor became so excited by learning how to run a business and worked so hard that in 1981, he and a partner opened a pub in Cincinnati.

A few months later, he was shocked to find out that the landlord had the right to take over the business (lesson: read the fine print in legal documents). He stayed on as manager, but it went bankrupt and the contractor who built it took over. Taylor convinced him to turn it into a rock club, but the killer hours and a pregnant wife persuaded him to quit.

In 1983, he got a job at a Bennigan's restaurant, getting hands-on experience in every position before being made bar manager in Dallas. But he didn't fit the corporate culture, nor that at Hooters and KFC, though his staff thought highly of him (lesson: have consistent one-on-one meetings to get to know workers).

He began thinking of creating a Texas-style steak place, where “good ol’ boys and girls” would be comfortable, as well as families. He pitched potential investors, including former Kentucky governor and KFC executive John Y. Brown. In 1991, they opened their first restaurant in Louisville, but reviews were poor (lesson: instead of discounts, focus on quality and service). Taylor finally sold his idea for Texas Roadhouse to the dentists and opened the first in 1992 (lesson: when times are tough, honestly analyze your strengths and weaknesses).

Taylor gradually created a unique business model and culture at the Roadhouse, going against the trends in the restaurant industry, like cutting portions and staff when things were slow:

- Keep prices low and quality high, sacrificing short-term profits to create long-term buzz (the Roadhouse does not advertise).

- Rely on time-tested recipes for dishes that are freshly made (don't follow food fads).

- Give away free peanuts, fresh-baked rolls, honey butter, and drink refills.

- Make it a fun place to work and visit (each plays upbeat country music or sports on TV).

- Only have three tables per server so they can provide legendary service (the industry standard is four to five).

- Welcome ideas for improving the business from every worker and keep raising the goals.

- To check out prospective key hires, dress down and talk to frontline staff at their current jobs (Taylor also went in disguise when he wanted to know how a particular Roadhouse was really doing).

- Have managers invest $25,000 to qualify to earn 10% of profits.

- Suppliers are partners — strategize with them on win-win plans in good and bad times.

- Don't punish risk-takers.

Taylor kept artifacts from his failed restaurants in his office, so he did not forget the lessons (including do better homework on the demographics and seasonality of location candidates). Until 1996, the Roadhouse was struggling just to pay its monthly bills, but he added a board of advisors and put together a private placement that paid off the debt in 1998.

By 1999, Texas Roadhouse had 45 locations in 14 states (but the one in Cincinnati was closed, the last for the next 10 years).

Rising to the Top and Going Crazy During the Pandemic

In 2004, the company began publicly trading as TXRH on the New York Stock Exchange, receiving an infusion of $183 million in new capital for its 183 restaurants. Split-adjusted, it started at $28 per share and recently clocked in at $96 per share.

"I recognize that for most founders, the story would end here," he wrote. "They'd take their share and retire to a nice cabin in the Poconos or on an island off Key West. I enjoyed the moment, but the next week I was back in my office moving full speed ahead."

In 2006, Forbes honored the Roadhouse as one of America's Best Small Businesses. ("I wondered how a billion-dollar business with almost 20,000 employees could be considered small," Taylor wrote.)

In 2011, it opened its first restaurant in Dubai; three years later, Taipei became its first East Asian location. By 2015, Forbes lauded it as one of America's Best Employers, and Restaurant Business News named it the top full-service restaurant in the nation.

Taylor was out of touch on a two-week ski vacation with friends in Austria through the first week of March 2020. and they did not watch TV or read newspapers since none of them knew German. On March 9, he arrived back in the office.

"I found our crisis people in action," he recalled. "Before this, we'd been having a record year … averaging more than $105,000 per week in sales, with most doing dinner-only service Monday through Friday and adding lunch on weekends. Overall, we had been up 4.5% over the previous year. As for to-go orders, they averaged just $7,000-$8,000 a store."

As sales fell off a cliff, he called JPMorgan to draw down a $200 million line of credit. He decided to forego his salary and make a $5 million personal donation to his nonprofit to help take care of employees during the pandemic. The company set up its own $11 million stimulus fund for hourly workers.

"I'd always encouraged our folks to keep an entrepreneurial spirit alive in their stores," Taylor wrote. "I often call the most creative, if not roguish, of our store managers and ask their opinions on new and innovative ways to operate our restaurants. I call this group my crazies."

To convert from 93% inside dining, Roadhouse began making madcap changes that had to evolve with local conditions:

- Learning from its Asian locations, it required workers to wear masks, gloves, and safety glasses, while thermometer-checks were required, social distancing enforced in small teams. It also gave out a list of safe practices when not at work, such as sanitizing doorknobs and gas pump handles.

- Packaged meals and ready-to-grill steaks were sold to newly-created drive-up areas (and later, frozen steaks, which it had never used).

- It used its influence to bring scarce food from its entire supply chain to where it was needed.

- Farmers markets were held in parking lots, even selling bags of produce.

- Arrangements were made for deliveries, including to first responders and the disabled.

- Some places showed movies on their outside walls and deployed carhops to serve food.

- When customers were allowed to dine inside according to local regulations, it played country music videos when there were no sports broadcasts.

"In a way, 2020 was the ultimate symbol of what we have created at Texas Roadhouse," Taylor wrote. "It was a year that showed our people's ingenuity and grit."

But then he was struck by COVID. His successor as CEO is Gerald Morgan, who started his career at Texas Roadhouse as the managing partner at its first restaurant in Texas in 1997 and was most recently president of the company.

His message in the final chapter: "Many rich people I've met seem quite unhappy … Joy, gratitude, social interaction, empathy, and helping others seem an easy choice to me over generating fear, anger, and sadness. Success is about achieving positive experiences and, here at the Roadhouse, that means creating one memorable meal at a time."

About the Author

Scott S. Smith has had over 2,000 articles and interviews published in nearly 200 media, including Los Angeles Magazine, American Airlines’ American Way, and Investor’s Business Daily. His interview subjects have included Bill Gates, Richard Branson, Meg Whitman, Reed Hastings, Howard Schultz, Larry Ellison, Kathy Ireland, and Quincy Jones.

Startup Resources

- Learn more about Startups

- Visit the TRUiC Business Name Generator

- Check out the TRUiC Logo Maker

- Read our Business Formation Services Review

- Find Startup Ideas

- Explore Business Resources

Form Your Startup

Ready to formally establish your startup? Click below to read our review of the best business formation services!

Best Business Formation Services