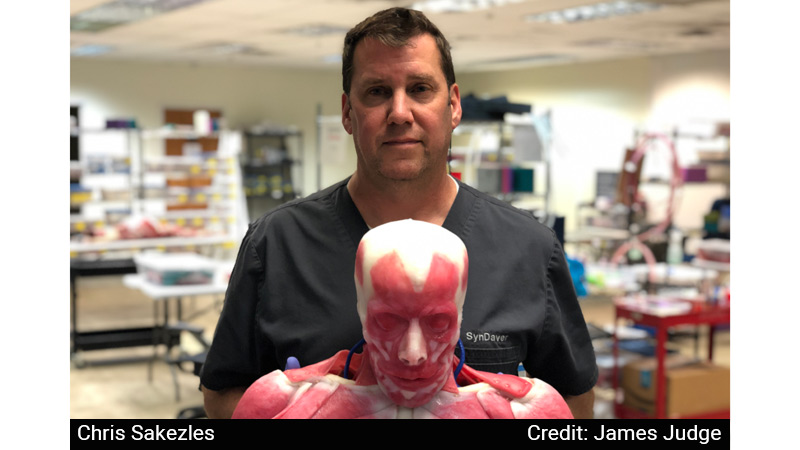

Christopher Sakezles's Synthetic Humans Are the Future of Medical Testing and Training

Christopher Sakezles seemed to have closed one of the biggest deals in the history of ABC's "Shark Tank" in 2015. The $3 million deal from Robert Herjavec was sealed for 25% of SynDaver, his Tampa-based startup which makes synthetic bodies for medical education and device testing.

"But the Sharks told me they felt I wasn't focused enough on making the company profitable for investors, since I wanted to keep reinvesting in growing our sales," Sakezles (pronounced sak-you-lees) told Startup Savant. "They wanted to replace me as CEO, but I own the majority of shares and I'm not the kind of guy that just does what he is told, so we could not come to a final agreement."

The Sharks should be regretting the one that got away, with sales this year on target to grow 40% over 2020 (when the pandemic kept them at a 7% increase, after several years at 40%). SynDaver's hundreds of clients include all the Fortune 500 medical device companies, the best medical schools and hospitals in the world, the US Food and Drug Administration, every branch of the US military, NATO, Underwriters Laboratories, Apple, Facebook, Google, Ford, GE, Procter & Gamble, and Nike.

When asked what Apple or Google might want to do with a synthetic body, mum's the word. "I had to sign pretty restrictive non-disclosure agreements, but I can say that many of these companies make products that have to be tested," he explained.

With appearances on TV shows like "Grey's Anatomy" and "CSI," its hyper-realistic cadavers have even entered popular culture as stars of the golden screen morgues.

Right now, even a Shark couldn't get in. Sakezles says he has raised about $2 million since launching in 2004, funding product development and expansion from profits. There is a line out the door for his next private offering, which is not yet even on the schedule, and another line that wants to buy the company.

Building a Better Body

Sakezles grew up in Tampa and earned a B.S. in mechanical engineering from the University of South Florida in 1991, a master's degree in materials science and engineering two years later at the University of Florida, and a Ph.D. there in polymer science in 1998.

It was in a 1993 class for his Ph.D. that he discovered how poor the options were for realistic medical testing. He had developed a new type of tube to insert into the trachea for procedures, but cadavers were expensive, quickly became unusable, and were hard to get (only about 20,000 are donated per year in the US and one has to be shared by four to six medical students). Of course, dead bodies did not respond like live ones and rubber parts were even less realistic.

His professor paid $3,000 for someone to build a fake trachea, but "it was such a piece of garbage I just threw it away," Sakezles recalled. He began developing his own, made of polymer fibers, water, and salts in a combination that mimicked live tissue.

After college, he worked for consultants in the medical device and pharmaceutical industries as he tinkered with his formula. After being fired due to a personality conflict with the boss, he decided it was time to get serious about his innovations and raised $600,000 from family and friends, then grew SynDaver from cash flow. "I was lucky to get fired because it pushed me to focus on what I really wanted to do," he said.

His first client was Johnson & Johnson, the biggest medical device company in the world, which was buying a lot of synthetic tissue for the groin. "I thought this would really capture the attention of investor groups, but none of them could see the potential," he said.

At one point, after a divorce, he found himself living in the office to save money. Development of a completely synthetic body was slow since it depended on modest early profits, taking 10 years instead of the two he had anticipated.

He finally made a sale to the US Army's Madigan Army Medical Center in Tacoma, Washington. It was priced at $25,000, below cost, but it lacked a head. Adding that and other improvements soon brought the ticket to $40,000. While cadavers (when one can get them) run $2,000 to $5,000, they aren't good for more than a few surgeries or tests, while syndavers are viable forever (they come with a service contract to be shipped back for periodic repairs).

The artificial bodies, hooked up to software, also respond similarly to patients who are still alive, including breathing, having a beating heart, and bleeding. Therefore, they are the better option, even where cadavers have been traditionally considered adequate for testing or training. Syndavers are increasingly popular for car crash studies. The company can also provide body types where cadavers are not available, such as infants (for legal reasons), or for pathological tissues that are hard to get (fibrous lesions on the uterus).

The top of the line standard synthetic body is now about $75,000, with 20 to 30 on the team creating it (all orders can be customized). The process of building one and maintaining it over time is now easier since the company began using a hybrid of wet artificial tissue and materials like silicone rubber. Sakezles says they have developed hundreds of different types of tissue analogues to create body parts (he holds 17 patents so far).

Initially, marketing was done by lending the artificial bodies to universities, which generated buzz and provided valuable feedback for further development. In 2013, Sakezles decided to send a photo of one to the Discovery Channel show "Mythbusters," and the resulting appearance generated media coverage that propelled sales over $1 million that year.

After filling out the "Shark Tank" application, he added a campy "mad scientist" video and shipped one of his syndavers to the producers, who called immediately. He was on stage for two hours, edited down to the 10 minutes that were broadcast, and while he received the initial offer, he admits he was not very articulate.

"I can't memorize lines to save my life," he told Forbes. "I'm a scientist, not a very public person. If you saw any of that segment, you could see I'm not a great communicator. They rapid-fire questions at you. Everything on the show is real. It's not staged or scripted. You don't meet the Sharks before the show or talk to them after."

But despite the failure to reach a final agreement, the resulting media coverage brought in $1 million from other investors.

The SynDaver Revolution

In recent years, Syndaver has launched synthetic dogs ($40,000), cats ($5,000), and frogs ($150). "The dogs are for surgical training in veterinary school, such as spaying, replacing an anesthetized dog, while the cats are simpler and primarily for high school anatomy classes," he explains of the price differential.

Students cannot keep an animal long under anesthesia, but cadavers are not an ideal substitute because they have to be defrosted and deteriorate so fast they do not provide a realistic suturing experience. Veterinarians have also praised the option of not using live animals because the type of student they would like to attract into the profession should be empathetic toward animals.

The company is divided into four parts: SynDaverX (which does custom work, about 30 jobs a year for the medical device industry currently), the government business unit (consulting for a handful of projects annually), the educational group (which makes and sells the synthetic humans and animals), and 3D printer group.

The company uses these printers in tissue creation and has discovered they are in high demand by other industries for their own 3D requirements. "It turns out we can make them cheaper and more reliable than anyone else and we expect this to be an important part of our overall business going forward," Sakezles said.

Even as it has grown fast, the number of employees has remained under 120, although he has plans for expansion, even to put offices in other countries. The potential, given the number of global markets it can address, is almost inconceivable.

But Sakezles isn't dazzled by the glamour of being a business leader. "CEOs don't really do all that much," he said. "We just build teams and make decisions. Fortunately, I've been blessed with a very talented and dedicated staff that makes my job easy. I think the CEO job is one of the first that will fall to artificial intelligence."

He doesn't anticipate changing his business model from building better bodies to an improved suite of managers; however, his hands are pretty full managing a new global industry.

About the Author

Scott S. Smith has had over 2,000 articles and interviews published in nearly 200 media, including Los Angeles Magazine, American Airlines’ American Way, and Investor’s Business Daily. His interview subjects have included Bill Gates, Richard Branson, Meg Whitman, Reed Hastings, Howard Schultz, Larry Ellison, Kathy Ireland, and Quincy Jones.

Startup Resources

- Learn more about Startups

- Visit the TRUiC Business Name Generator

- Check out the TRUiC Logo Maker

- Read our Business Formation Services Review

- Find Startup Ideas

- Explore Business Resources

Form Your Startup

Ready to formally establish your startup? Click below to read our review of the best business formation services!

Best Business Formation Services